Kennedy Approach - guide

In the game Kennedy Approach, we play as an air traffic controller. An air traffic controller is a profession as exciting as it is lucrative. The attractiveness of the game is enhanced by a decent simulation of human voice and a high level of program realism, despite the symbolic yet clear graphical representation.

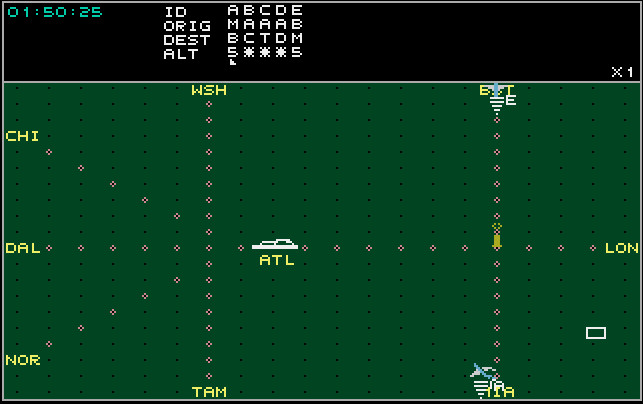

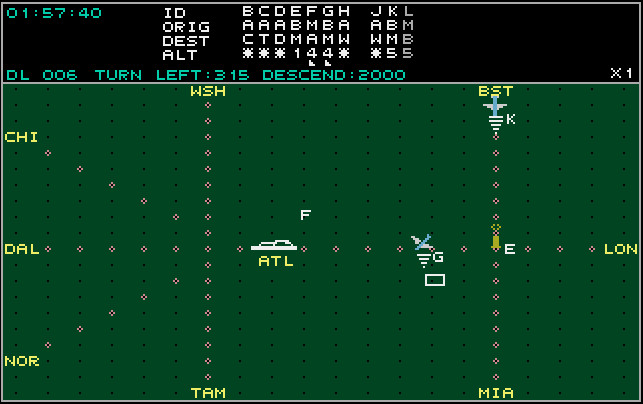

On the map of your airport's area, a grid is overlaid— the distance between two adjacent points vertically or horizontally is 1 mile. The distance between points measured diagonally is about one and a half miles—this is the radius of turn for each flying machine (45°). In front of the airport is the control tower with radar. Main communication routes are highlighted, which departing aircraft must use from your area.

Above the map, data on aircraft controlled by you appear. The highest displayed is the alphabetical identification symbol of the aircraft, assigned alphabetically to the successive aircraft reporting. You can call each of them using this symbol. Below are the first letters of the code of the home and destination airport. If both are the same, it means it's a recreational aircraft on a sightseeing flight. This does not mean it can be disregarded.

Altitude—this is the distance of the aircraft from the ground in thousands of feet. An asterisk in this position indicates waiting for takeoff. Data about the aircraft disappear after landing or leaving your airspace.

In the upper left corner, there is a real-time clock. The full hour ends your shift. This moment can be accelerated using the SPACE key—time will start to flow faster. Alarm messages are displayed in the window below the clock.

The most popular aircraft on intercontinental routes are Jet aircraft, mainly represented by Boeing products. Their cruising speed is about 4 miles per minute. Occasionally, French Concorde aircraft arrive from the old continent, with a supersonic speed of 8 miles per minute. They stand out in size, wing shape, and characteristic, sharply curved nose. Somewhere between them, small private planes weave through the sky at a pace of 2 miles per minute. All aircraft reach a maximum altitude of 5000 feet. Under the directed nose towards the flight direction of the aircraft silhouette, there is a scale indicating its altitude. It is worth knowing that the exact position of the aircraft is determined not by its silhouette but by the lowest line of the scale.

Each aircraft approaches at an altitude of 5000 feet, reporting about a minute earlier. Without receiving instructions, it will circle at a constant altitude around the VOR until it runs out of fuel and descends. A proper landing should take place from the direction of the control tower at an altitude of 0 (CLEAR for LANDING). It is important that an aircraft approaching for landing does not accept course change commands—maneuvers are only executed after increasing altitude.

If the runway is occupied by landing or departing aircraft, you can instruct the pilots to circle around the control tower (HOLD AT VOR) to the left or right. While waiting for a free runway, the aircraft may decrease altitude in preparation for landing. Unfortunately, circling around the tower is treated as a delay, which affects the final assessment of your skills.

Aircraft departing from your airport or just passing through your area must leave at an altitude of 4000 feet to maintain safety at the region's border. Aircraft should also not fly over mountains at altitudes below 4000 feet—otherwise, there is a risk of crashing into the slope. Reserved sectors are dangerous— the appearance of an aircraft over the White House in Washington results in its shooting down by security services. Also, entering a storm area usually ends in an emergency landing.

Regulations state that the distance between two aircraft must not be less than 3 miles, or they must be separated by a difference in altitude of at least 1000 feet. Violation of this rule results in sirens blaring and a state referred to as a conflict by professionals. The system was supposed to prevent collisions in theory, but practice shows its redundancy in completely safe situations. Nevertheless, the total sum of conflict minutes is a scoring criterion, which is of considerable importance.

A notable problem is: Emergency! Eight minutes of fuel. This message is reported by the captain of an aircraft that can only stay in the air for 8 minutes. Such an aircraft cannot be sent out of its own airspace because it risks an influx of low-fuel machines from other sectors. Furthermore, quickly dispatching a troublesome aircraft far from your own airport risks accusations of ordering a sector evacuation for a threatened aircraft.

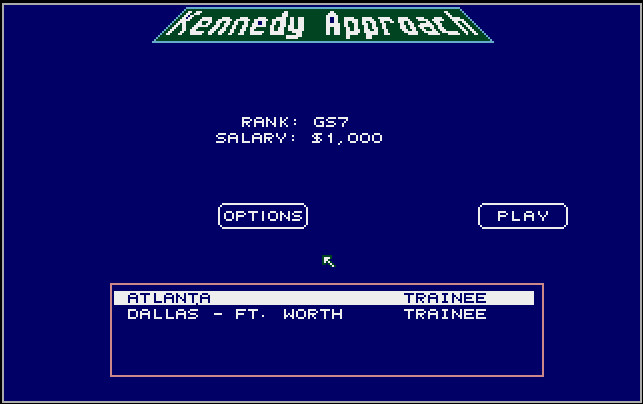

You can work in one of the five American airports at various levels: training, night shift, morning and afternoon hours, and peak load. Your shift is summarized in terms of conflicts, delays, disasters, improper exits from the sector (incorrect altitude, speed, direction, etc.), exits with risk, and the number of properly handled flights.

Useful information: a long press of the action button (or fire on the joystick) is a request for status from the selected aircraft. This will help you maintain orientation in heavy traffic.

Below is the access code table: